I Love Every Person's Insides

On SOPHIE, digital performance, and formulation of identity through online spaces

2023-06-21, originally published 2021-02-12

This is an article I originally wrote and published to substack under the nom de plume "Beeves Montgomery" on February 12, 2021, thirteen days after SOPHIE tragically passed away. SOPHIE is one of my favorite musicians of all time, and the amount of influence she's had over the way i listen to, think about, and make music is nearly unrivaled by any other musician. I was gutted when I found out she had died, and in the following weeks, I was compelled to do something, anything, to monumentalize the impact she had on my life. This is the first, and to this date only, longer-form piece I've ever published about music. There are some portions I look back on and cringe, but overall, I'm very proud of what I was able to articulate in this article. I'm reposting it here just because it feels a lot more personal to host it here than on some substack account that I'm never going to touch again. This article has been modified gently to make the HTML work on my website, but the textual, pictoral, and video elements remain unchanged.

Back in the autumn of 2017, SOPHIE released the music video for “It’s Okay to Cry,” her first single from her upcoming studio album Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides and her first solo release since her 2015 compilation Product. The video showcased her against an ever-shifting sky, singing a ballad about the joy and beauty of being emotionally vulnerable to a softer, more dramatic iteration of her signature synthpop instrumentation. In this video, she seems euphoric, caressing her own shoulders, scarcely breaking eye contact with the camera, smiling with glee as she belts out her ode to self-acceptance.

The release of this video marked several firsts in Sophie’s career. It was the first time she had ever used her voice on any of her songs. In all of her previous work, the vocals were done by uncredited guest vocalists. Even outside of her music, she avoided having her natural voice be associated with her public persona. In a 2013 phone interview with Skream and Benga for BBC Radio 1, Sophie fed her voice through a vocoder that made her sound like a five year old girl. (When inquired about her inflection, she simply responded that she had “a bit of a cold.”) It also marked the first time she had ever purposefully associated her face with any of her music as SOPHIE. Prior to “It's Okay to Cry,” she would perform DJ sets in clothing that concealed her face. In her 2014 Boiler Room DJ set, she hired a drag queen to pretend to be her while Sophie disguised herself as a security guard.

Sophie’s reclusiveness prior to the release of It’s Okay to Cry led to a lot of speculation around her identity, not an uncommon trait amongst British electronic musicians. The best hint as to her true identity came from Skream in the aforementioned BBC Radio interview, where he hints that SOPHIE was a Scottish man. This led to a lot of controversy around her, with artists and journalists accusing her of using her moniker, feminine voice-tuning, and signature bubblegum pop sound as “appropriation of femininity,” an accusation that, in retrospect, was fairly transphobic. However, following the song’s release, she became a lot more forthcoming with her identity. She would conduct a lot more in-person interviews where she would talk about being a transgender woman, and express an interest in “using her body” more during live performances. A lot of these interviews also featured photoshoots. It became clear she gained a lot of confidence in her identity and presentation in the years following the release of Product. Sophie notes that a lot of her fans and music journalists interpreted these aforementioned firsts in “It's Okay to Cry” as her coming out of the closet as a trans woman.

However, I believe those people are wrong. The release of “It’s Okay to Cry” was not Sophie’s “coming out” event because Sophie rejected the notion of “coming out” for herself. Here is an excerpt of her Teen Vogue interview where she touches on the subject:

“I don’t really agree with the term ‘coming out’.… I’m just going with what feels honest…. I certainly feel more happy presenting myself.”

Sophie’s rejection of traditional notions of “coming out,” i.e. that one pivotal moment where you make your queer identity known to the world, is what I believe to be a component of the central message of Un-Insides. Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides is an album about the unique terrain that online spaces and digital technology create in terms of finding one’s own identity, and how that has related to Sophie’s own identity.

I first want to touch on the development of electronic music, specifically the electronic music coming out of the UK rave scene in the aughts, and how the rapid advancements of internet technologies affected that development. Take dubstep for instance, a musical genre that began around the turn of the century and combined the erratic rhythms of 2-step with dub, a subgenre of reggae that manipulated reggae samples by increasing its bass, reverb, and echo levels. While dubstep was initially relegated to local scenes, its main impetus towards gaining international acclaim was online spaces. Websites like Pitchfork and dubstepforum piqued a larger interest in dubstep, and the popularity of bittorrent clients and quasi-legal file sharing services like Megaupload and Napster gave interested listeners access to that music. By the teens, dubstep was an international, popular music genre, featuring superstars like Skrillex snatching eight grammys. Today, its influence is felt in genres ranging from EDM to trap to pop. (Whether this is a good thing or not depends on the dubstep fan you ask.)

This trend is very universifiable to the music industry at large. Since the turn of the century, the main modality of music consumption has shifted from CDs and tapes to mp3 players to streaming services, for better or worse. Each iteration of this shift has mandated decreasing amounts of dedicated hardware from the end-user, with forms of music consumption that require high amounts of physical space, such as vinyl records, having become relegated to niche modalities of consuming music. The popularity of upload/streaming services such as Soundcloud and Bandcamp combined with the widespread access to Digital Audio Workspaces such as Ableton, FLStudio and GarageBand have created a booming ecology of electronic music in online spaces. This has even resulted in genres that develop entirely online like hyperpop, a genre that Sophie herself seeded the existence of.

That online ecology is what gave birth to SOPHIE: the first song she ever released under her all-caps moniker, “Eeehhh,” was released through her SoundCloud in 2011, and would later reappear as the B-side of her single “Nothing More to Say” in 2013. Given how Sophie’s music was mostly released and popularized through online media and spaces, as well as the stark contrast between her real-life reclusiveness and her vivid, maximalist, and energetic music, I believe that those online spaces provide a valuable context to Sophie’s music. And if you choose to view the art that one makes as an extension of their own identity, then this would bring rise to identities shaped and molded by online spaces.

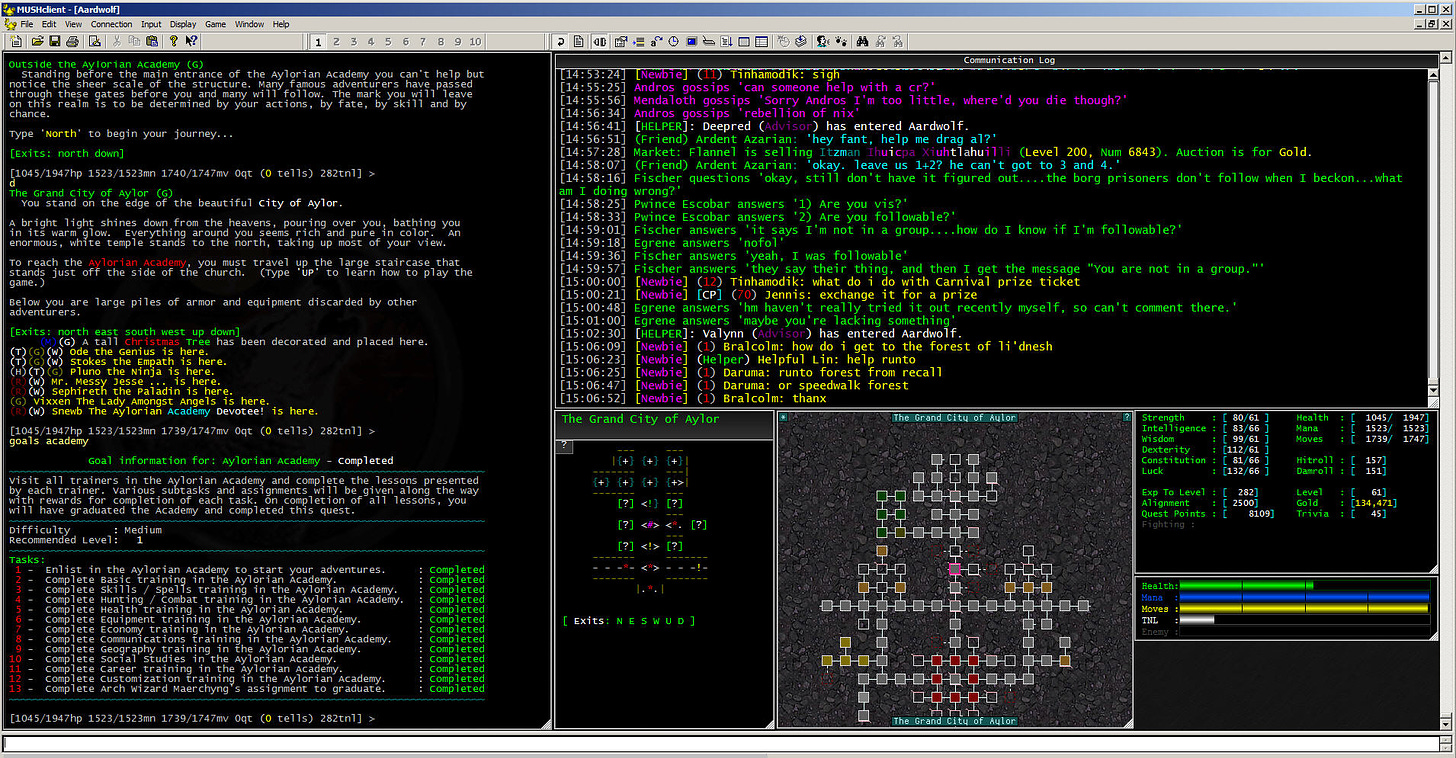

But what is so disparate about the effects online spaces have on one’s identity that they warrant this analysis? What separates formulation of the URL self from the IRL self? To answer these questions, I want to turn to sociologist Sherry Turkle, who wrote extensively on the subject of digital performance and identity in the 90s. Her research mainly focused on players of Multi-User Dungeons, or MUDs: text-based online role-playing games that were precursors to the more ubiquitous MMORPGs of today. While the internet Turkle analyzed was one in relative infancy compared to the internet we all interact with daily these days, I still believe that her tenets of digital performance ring true to this day. In fact, I believe that what Turkle documented was the dawn of certain kinds of social relationships with computers that have only expanded in scope and intensity since then.

Turkle notes the potential of MUDs as a way for the player to “remake the self” in “Constructions and Reconstructions of Self in Virtual Reality.” Within the space of the MUD, the player has a lot more autonomy over how they present: they can choose their own name, history, even personality. She further extrapolates this remaking of the self within the virtual space as a vehicle for self-reflection and formulation of identity. The virtual self mirrors the real self in the choices and interactions with other players in the virtual space, and this allows for inner fantasies and realities to become discovered or better enunciated. This is accomplished in part by two things online spaces provide, according to Turkle: anonymity and multiplicity.

In Turkle’s 1996 article “Who Am We,” she touches on performance of gender through digital spaces in the form of what she refers to as virtual gender-swapping, specifically male MUD players who role play as female characters. She notes that it is easier for men to perform femininity through the MUD than it is for them to do so in real life, where they run the risk of being subjected to violence and arrest. She ends this segment of the article by saying this on virtual gender-swapping:

“[Virtual gender-swapping] can be psychologically complicated. Taking a virtual role may involve you in ongoing relationships. You may discover things about yourself that you never knew before.”

The bush that Turkle is beating around, obviously, is the possibility that when someone roleplays as a gender not assigned to them at birth, they may come to realize their own gender is not the one assigned to them at birth. This confounds the gendered relationship between the digital self and the non-digital self. The terrain and options that online spaces provide in expressing gender can be used in formulating the gender identity of the user.

But that distinction between the self in the virtual space and the self in the meatspace is not so rigidly defined; after all, they do both comprise the self, just in two different contexts. With our online selves and interactions becoming more tied to our offline selves, and virtual technology mediating over more and more of our lives, those contexts become increasingly intertwined. It would be reductionist to compartmentalize online interactions as being fake or meaningless, especially during a time where in-person interactions come with the threat of illness or death. But while intertwined, these contexts still do ultimately remain separate. We are allowed some degree of autonomy in how connected our online presence is to our offline identity (for instance, “Beeves Montgomery” is not my real name). This intertwined-yet-separate relationship allows for self-reflection and discovery through virtual interactions to occur on more frequent and deeper levels, without doubt stemming from the “fakeness” of the realities associated with these discoveries.

Deconstructing the disparity between the natural and synthetic is one of the central motifs of Sophie’s music, but more on that in a future article. Sophie references that disparity directly in the upbeat, staccato pop banger “Immaterial,” which reads:

You could be me and I could be you

Always the same and never the same

Day by day, life after life

Without my legs or my hair

Without my genes or my blood

With no name and with no type of story

Where do I live?

Tell me, where do I exist?

I believe the “me” and “you” she mentions in this song both refer to herself, further reinforced by “life after life,” referencing the two lives she has led up to this point: one as Sophie, and the other as SOPHIE. Without my legs or my hair, without my genes or my blood implies this other self is metaphysical, i.e. virtual. She ends the verse by expressing confusion at where she exists. How can her physical and metaphysical selves coexist without causing her conflict? This question is rectified in the pre-chorus, where Sophie realizes the permutability of her own identity. I can be anything I want, anyhow, any place, anywhere, anyone, any form, any shape, anyway, anything, anything I want.

That permutability of identity compromises much of what she is trying to convey in Un-Insides. She both expresses fear in its possibility in “Is It Cold in the Water?” and celebrates its legitimizing nature in “Faceshopping,” the album’s third single. The lyric video for “Faceshopping” is a collaboration between Sophie and Argentinian CGI artist Esteban Diácono. The video starts showing a 3D model of Sophie’s face behind rapidly flashing lyrics in Futura Extra Bold. After the first chorus, the 3D model of her face twists and distorts like balloon rubber, melts like candle wax, and slices into pieces, all interspersed between ascetic makeup advertisement photography, a video of a cuttlefish, social media logos, and someone clicking a reCaptcha “I’m not a robot” box.

This fixation on the face comes from the face as the most base-level indicator of personal identity and inseparable from one’s real-world presentation. On the other hand, one’s virtual presentation is not tied to their face unless they choose it to be so. Recreating Sophie’s head in 3D animation software, a virtual space, and subsequently distorting and destroying her Houdini-recreated head deconstructs and blurs the lines between these two contexts she exists in. She expands on this concept within the lyrics of the chorus:

My face is the front of shop

My face is the real shop front

My shop is the face I front

I'm real when I shop my face

Breaking the chorus down line by line, I interpret the first two lines to mean the same thing. Storefronts are the first thing that people notice about a business and are meant to entice potential customers, functioning as an impetus for future transactional relationships: goods and/or services in exchange for money. Given that transactional relationships are considered shallow forms of relationships, as well as her use of “real” in line 2 (it’s worth noting that every use of the word “real” in the lyric video is represented in the style of a Coca Cola advertisement), Sophie is saying that there is some aspect of her real-life presentation and persona that is disingenuous. The third line ascribes a different meaning to “shop” than the previous two: shop in this context refers to the body of work she makes a living off of creating. When Sophie says My shop is the face I front, she is saying the most base-level indicator of her identity has been through her music. The larger view she has on formulating the self is exemplified in the last line of the chorus: I’m real when I shop my face. Interpreting “shop” in this context to mean alter, i.e. Photoshop, Sophie is saying she is her most authentic self when she is constantly changing the ways she makes her essentiality known to others.

This is why Sophie doesn’t agree with the term “coming out.” She never came out because her transness was evident from the moment she first posted “Eeehhh” to her soundcloud in 2011. Her music was the modality through which she lived and expressed her gender, all made possible through the terrain that online spaces have provided in formulating her identity. Sasha Geffen, the journalist who profiled Sophie for Vulture, puts this better than I ever could:

the impact of sophie isn't just 'representation' it's that she had started to figure out how to translate these hidden processes of perceiving & becoming into music

— skrillex guattari (@sashageffen) January 31, 2021

Instead of being her “coming out” event, the release of Un-Insides marks a resolution of the conflict she described in “Immaterial”: her digital and physicals selves began to resemble each other more, and in turn, they began to exist in harmony. The narrative of self-creation and acceptance Sophie expresses through her music is one of more gradual shifts and changes towards a more actualized and honest self. These changes are made possible by the anonymity, multiplicity, and autonomy virtual spaces provide. This mode of identity formulation is common amongst younger queer and trans people; the number of trans Sophie fans that have expressed how her music helped them realize or feel comfortable with their own transness speaks to that universality.

I wanted to end this article on a personal note. I lost an idol of mine. I have wanted to write about her music for a long time, and I am doing it now as a way to celebrate her life. But in celebrating her life, it feels like I am keeping myself from fully acknowledging her death. Whenever I dwell on it for too long, it feels so completely inconceivable that she’s gone forever now.

Even as we live through a time in history where mass death is a daily event, almost to a desensitizing level, it feels almost insulting to hear about the way she died. To think that someone so brilliant and impactful could die in such an abrupt, meaningless way. I suppose that’s the thing that everybody realizes about mortality that we always eschew thoughts of when they arise: there is nothing you can do in your life that will keep you from an untimely, abrupt, and meaningless death.

I hope that when she died, she was aware of even a fraction of the impact that she’s had. I hope she had some idea about the sheer number of people who started making music because of her, myself included. Of how many trans people became able to articulate their existence because of her music. Of how she shifted discussions of what pop music can do, can mean, and can be decades ahead of its natural course.

I’ve found myself these past couple of days flipping through my rolodex of memories of her these past couple of days. The shock and intrigue I felt hearing “HARD,” my introduction to her music, for the first time. Dancing to “VYZEE” and “Immaterial” in my friend’s basement. Creating apocalyptic robot fantasies in my head to “Whole New World/Pretend World.” Trying to imitate the Lÿno font in my school notebooks. Endlessly tweaking my bass lines in Max/MSP to get them as punchy and energetic as the ones in “Nothing More to Say.” How excited I got when I found out Un-Insides was nominated for a Grammy. All of the moments I have spent with her music have helped me understand myself and my place in the world better, helped me hone my craft as a musician, but more than those things, those moments made me so happy. Her music provided me with such raw, unbridled joy during the times in my life when that joy was hard for me to come by. Thank you for that, Sophie. Thank you from me and everyone whose lives you’ve touched.

Special thanks to Samu Terwilliger for editing and to Kara Webb and Danielle Jean-Baptiste for feedback.